Last week at the ATIA conference in Orlando, I heard a concept described in a way that instantly made me pause—in the best way.

It wasn’t new information, exactly. It was a new frame for something we’ve been saying for years.

Samantha Hagness and Becky Woolley, AT Specialists in Mesa Public Schools, presented a session called “Sustainable AAC Starts With Staff: Strategies for Building Capacity. They asked us to consider that word, “modeling” and why at times our instruction to communication partners may be misunderstood.

In AAC, we talk about “modeling” all the time. And I’m starting to think that word is working against us.

The problem with “modeling”

In everyday teaching language, modeling has a pretty clear meaning:

“I show you how to do it… and then I expect you to do it.”

That’s the classic I do → we do → you do framework.

And for many teachers (especially special education teachers who were trained well and are doing their best), that’s exactly what “modeling” implies: demonstration followed by performance.

But here’s the disconnect:

When AAC professionals talk about “modeling,” we usually mean aided language input—using the student’s AAC system in front of them to show language, without requiring a response.

That’s not “I do, you do.”

That’s “I communicate… and you get to watch what communication looks like on your system.”

So when we use the word modeling, we may be accidentally communicating something we don’t actually mean.

And that matters—because words shape expectations.

What we really want: AAC immersion

If I could wave a magic wand, I’d replace the word “modeling” (at least in family- and teacher-facing conversations) with something that better reflects the no-demand nature of aided language input.

One option I keep coming back to is:

AAC Immersion (or Immersive AAC Input)

Because what we’re really trying to create is an environment where the student is repeatedly exposed to functional AAC use—just like spoken language learners are exposed to spoken language all day long.

Not a lesson.

Not a test.

Not a “show me you can do it.”

An environment.

Why immersion is how humans learn language

Language isn’t a “special skill” with a unique learning rule. It’s a human skill. And humans learn language by living inside it.

Think about how you learn other skills. When you got your driving learner’s permit at 16 years old and sat behind the wheel for the first time, you weren’t starting from zero. For years, you had been “studying” driving without anyone calling it that:

• You watched adults get into the driver’s seat.

• You saw them put the key in the ignition (or push the start button).

• You noticed the mirror checks and the shoulder glances.

• You watched hands turn the wheel—and saw what happened when the wheel turned.

• You learned what “stop,” “go,” “slow down,” and “we’re going to be late” sounded like in real life. (And yes… you probably learned a few words you weren’t supposed to learn, too.)

By the time you took the wheel, your brain already had a framework for what driving looked like.

That framework matters because humans learn by attaching new learning to old learning. We build mental maps by connecting what’s new to what’s familiar.

Now let’s compare that to many AAC users.

Our AAC learners often do not live in an environment where people around them communicate using AAC.So we place a robust language system in front of them—and then wonder why it’s so hard.

It’s hard because they don’t have the “car ride” experience. They don’t have years of watching communication happen in the same modality they’re expected to use.

The second-language example we all recognize

We also know this is true in other learning contexts. The best way to learn a second language isn’t memorizing vocabulary lists. It’s immersion. Over the years, I’ve asked participants in trainings a simple question:

“How many of you took classes in a second language?”

Almost everyone raises a hand.

Then I ask:

“How many of you feel like you’re an effective communicator in that language?”

Very few hands go up.

And almost every time, the people who do raise their hands have one thing in common: they spent meaningful time immersed in that language—living where it was spoken, hearing it constantly, watching it used for real purposes with real people. AAC is no different.

Why this terminology shift matters

When we keep saying “modeling,” teachers and families may hear:

• “I’m supposed to teach them to press buttons.”

• “I’m supposed to prompt them to repeat it.”

• “I’m supposed to get data on whether they did it back.”

And that can accidentally create performance pressure—especially for students who are already dealing with motor planning demands, cognitive load, sensory stress, and the vulnerability of being watched.

AAC immersion communicates something healthier:

• “I’m going to use AAC around you.”

• “You’re going to see what communication looks like on your system.”

• “You can join when you’re ready—no pressure, no ‘say it,’ no demand.”

That shift supports dignity, reduces pressure, and increases opportunities for authentic communication.

What AAC immersion can look like (in real life)

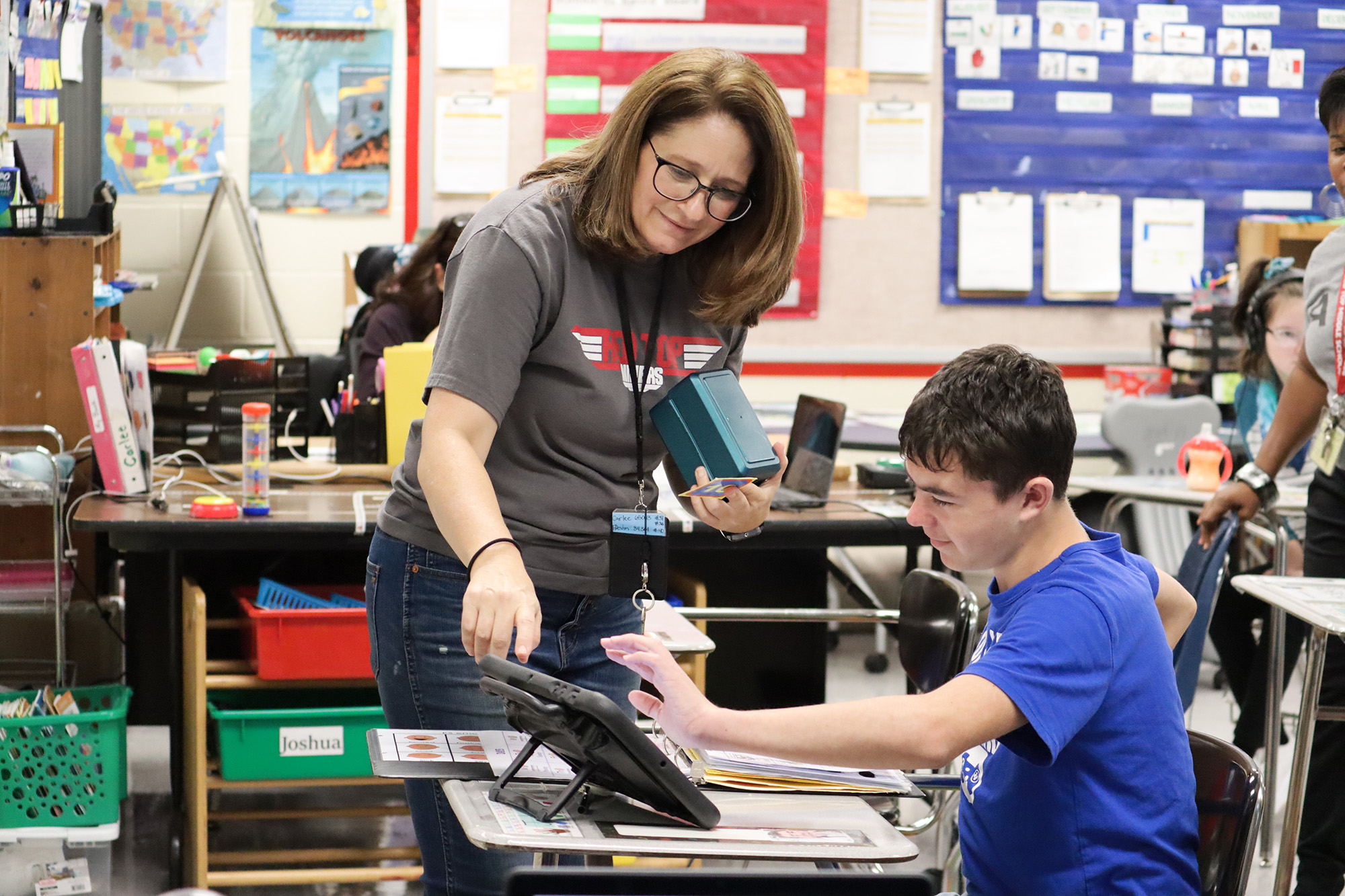

AAC immersion doesn’t have to be complicated. It’s small moments, repeated often:

• Commenting during routines (“That’s funny.” “I like it.” “Not yet.”)

• Making choices without requiring a “correct” response (“Do you want music or game?” and then selecting your own message, too)

• Using AAC when you’re frustrated (“Wait.” “I need help.”)

• Narrating what’s happening (“Go.” “Stop.” “All done.” “Again.”)

• Showing social language (“Hi.” “Miss you.” “Your turn.”)

The goal is not “copy me.” The goal is language exposure with meaning.

A question I want you to consider

So here’s my ask for you—parents, teachers, SLPs, paras, everyone supporting AAC users:

What term could you use that better communicates what we really mean?

Because if “modeling” makes people think demand, performance, and repeat after me… then we may need language that makes people think:

exposure, environment, immersion, and opportunity.

If you try out AAC immersion (or another term you love), I’d genuinely like to hear what resonates—and what your teams respond to best.

The words we choose shape the culture we create.

And our AAC learners deserve a culture where communication is something they get to see, experience, and grow into—not something they’re constantly asked to prove.